(Note: This post contains affiliate links. As an Amazon associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. That means if you click on a link and make a purchase, I will get a small commission at no additional cost to you. To learn more about why I use affiliate links, you can read my disclosure policy. Thank you for supporting Building Savvy Learners.)

Executive Function Challenges When Setting Student Goals

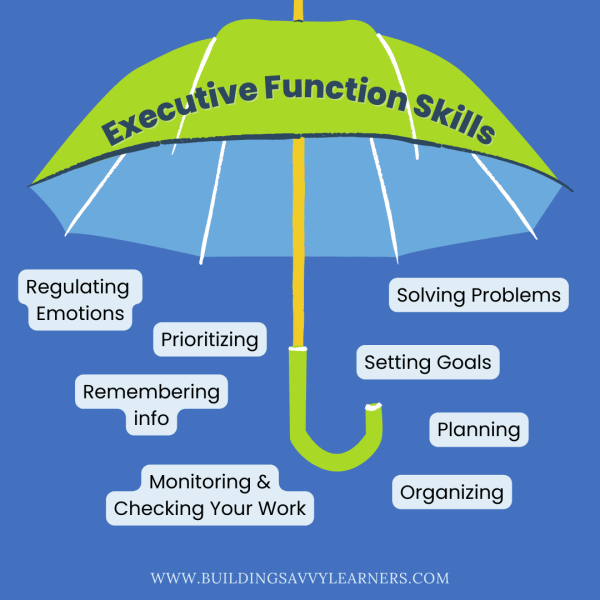

When considering the umbrella of executive function skills, there are lots of potential pitfalls. Fundamentally, students with weaker executive function often struggle to set goals because they have a harder time visualizing outcomes. They have a harder time thinking about a realistic outcome in the time available to them. Once they have the goal, they may struggle with breaking down the component steps needed to accomplish the goal. They may also encounter lots of executive function hurdles along the way.

Planning & Organizing

Prioritizing

Solving Problems & Regulating Emotions

Monitoring & Checking Your Work

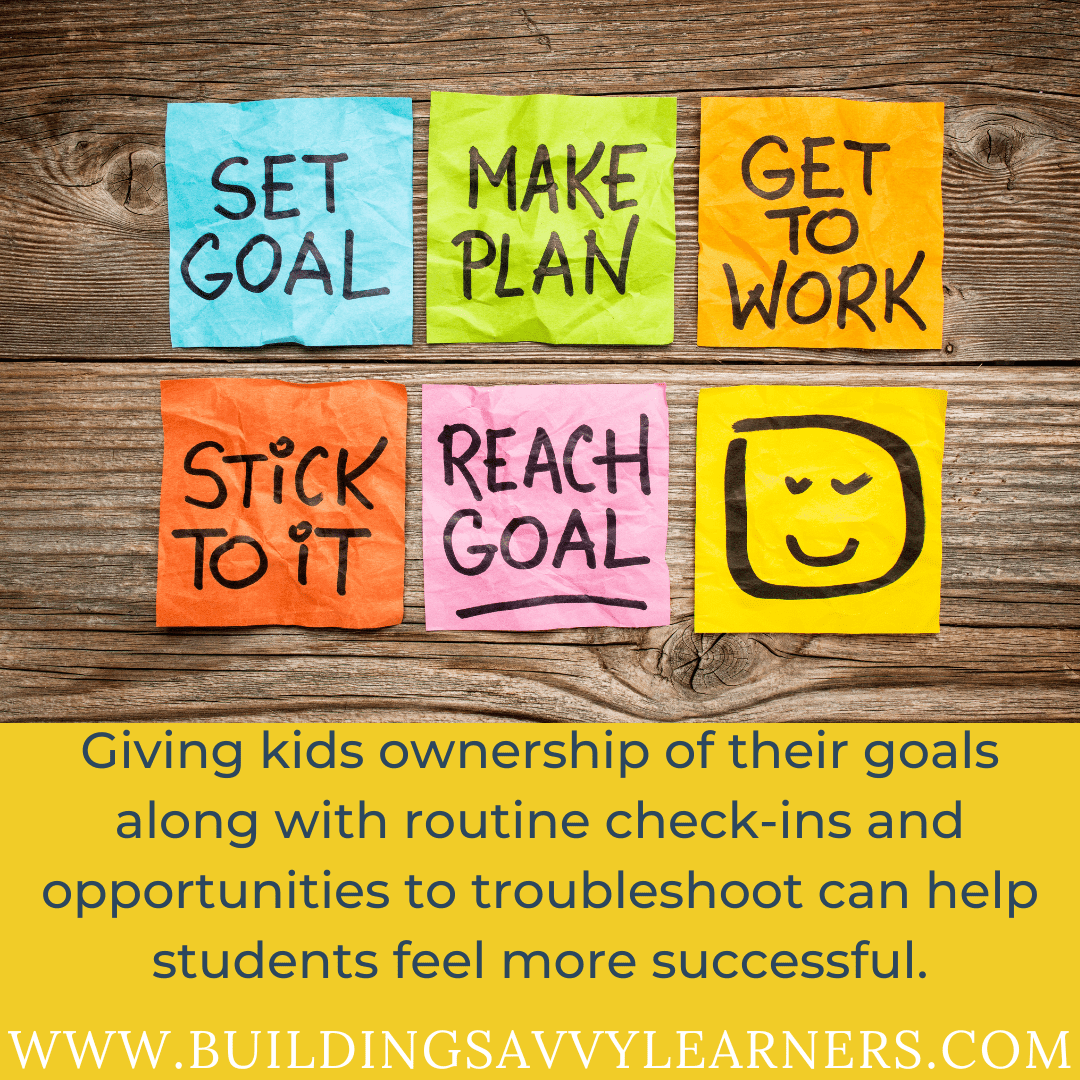

Strategies for Student Goal Setting

Outcome-Oriented Goals

Outcome goals are goals that are only achieved by accomplishing a specific result. For example, “Get all A’s this semester” or “Lose 40 pounds.” The problem with these types of goals is that intervening variables can derail the outcome and make the student less than successful. It may also be harder to track progress on the way to achieving the goal. The student seeking all As, for example, could be working hard and have a B+ going into finals, and then be thrown off by a question on the final exam. If the student still finished with a strong B, that’s not a failure — especially if the B was an improvement over previous grades. But they might see that they failed to meet their goal and suffer another blow to their self-confidence.

The other downside to these outcome-based goals is that sometimes students settle for less than they’re capable of. When students have struggled with self-esteem issues related to poor executive functioning, they may doubt what they can accomplish. As a result, they might set a goal to get B’s in their classes when they could be getting A’s. We want the goals to be realistic and achievable so that students experience success, but we don’t want the goals to allow them to underestimate themselves.

Process Goals

Process goals focus on completing particular actions regardless of the ultimate outcome. For example, “write down homework assignments for every class in my planner” or “study at least one hour every night.” These are items generally within the student’s circle of control, so they can be held accountable for their actions.

These are the kinds of goals that ultimately create a foundation for future success. Often students will immediately see results from their actions, and that can also help build motivation and momentum to continue. The student who sets a goal of studying for at least 90 minutes every night may find themselves performing better in their classes, for example. As a result, they’ll be more likely to continue working on the process goal because they’re experiencing natural feedback within their environment.

Tips for Achieving Long-Term Goals

Give Students Ownership of the Goal

Strive for Self-Improvement

As students set goals for themselves, they should strive to improve upon where they’ve been. In the best-selling book Atomic Habits, James Clear argues that if you improve by just 1% each day over the course of the year, you will be a whopping 37 times better at the skill by the end of the year. While it may be hard to get 1% better at some process goals, students should find ways to compare their performance to previous accomplishments. Depending on the goal, students can keep track of their progress to show how they’re improving from week to week.

Streaks can be another way to show self-improvement. For goals like writing down all homework assignments, students can track how many consecutive days they do it or how many days out of the week or month. Then they try to beat their previous record. There’s power in momentum and seeing yourself accomplish more than before.

Identify Milestones Along the Way

Develop Accountability Checks

When you’re teaching a young person to set goals, it’s important for them to see examples. Consider having everyone in the family set and openly share a goal at the start of the semester. Keep those goals posted in a prominent place like the kitchen or near the launch pad, and use that posting as a visual reminder to check-in with each other to find out how things are going. Having discussions centered around goal progress can build accountability toward accomplishing that goal.

Sometimes students respond better to a non-parent as an accountability buddy. If they’re not making the progress they want or think parents expect of them, they may have a harder time acknowledging obstacles and troubleshooting problems that arise. They may say that everything’s “fine” even when it’s not. In those instances, it may be helpful to enlist someone like an executive function coach to help with those discussions. A coach can help build the self-awareness needed to overcome the executive function challenges.